In past years, I’ve given homemade vanilla extract and ten-packs of soup and certificates for babysitting services. More recently, I’ve made personalized cryptic crosswords. (You can get my 2017 Christmas Cryptic here.)

As kids, we were taught that the best Christmas gifts are made rather than bought, and although my lack of artistic ability should have put pain to that lesson long ago, I’ve never been able to shake it. In past years, I’ve given homemade vanilla extract and ten-packs of soup and certificates for babysitting services. More recently, I’ve made personalized cryptic crosswords. (You can get my 2017 Christmas Cryptic here.) But this year, fascinated by the concept, I decided to try my hand at something considerably more involved: a personalized escape room.

3 Comments

Ice cream made with liquid nitrogen Ice cream made with liquid nitrogen Saturday last, at the Concordia University Exposcience event, my three-year-old figured out how to accelerate and decelerate her heart rate on an ECG by imagining infuriating or calming things. She pulled all the organs out of a model of a human torso, then reassembled them. She controlled a robotic car and accepted a helium balloon and made fractal art but given that she is three, her favourite part was sampling the ice cream made from liquid nitrogen. Of all the demonstrations, my favourite was from the cool cats from the Concordia Chemistry Department. They held a seemingly blank piece of paper over a flame (careful not to burn it) until a hidden message appeared.  Lemon juice was the invisible ink in that case, and it gave me a geeky thrill to see the trick in action. But it still didn’t beat the subterfuge of another hidden message I saw recently. Vexed by President Trump’s failure to condemn rioting white supremacists in Charlottesville, Virginia, all thirteen members of the U.S. President’s Committee on the Arts & the Humanities (which included actor Kal Penn and Pulitzer prize-winning author Jhumpa Lahiri) resigned en masse in August. Their resignation letter was scathing and formidable. (You can read it here.) But that wasn’t all. Embedded inside the letter was a hidden message: the first letter of each of the paragraphs of the letter spelled the word “RESIST”. Maybe three days later, the Science Envoy for the Department of State, Daniel M. Kammen, also resigned. His letter contained the acrostic “IMPEACH”. Of all the riddles used in cryptics, I find initialism clues and hidden word clues the most delightful because of the way they manage to hide in plain sight, effectively using the words around them as camouflage. But acrostics, which are concealed messages made up of the first letter of every word, sentence or paragraph, can add another mind-blowing dimension. Read the source material and you get one message. But read the acrostic and it can give you a thought-provoking, even jarring new perspective. Examples of acrostics abound, from the Edgar Allan Poe poem (unimaginatively named “An Acrostic) that spells out "ELIZABETH" to the memo from the CEO of Sun Microsystems, which contained the acrostic "BEAT IBM". But the best example I’ve found to date of an acrostic that completely changes your take on things is in Vladimir Nabokov’s 1958 short story “The Vane Sisters”. The story, told in the first person, is about a man who has just learned that a former student with whom he had a brief relationship, Cynthia, has died.  Cynthia, whose sister Sybil commit suicide, was a believer in spiritualism and the occult, and was convinced that the dead send messages to the living, sometimes through acrostics. After the narrator learns of Cynthia’s death, he become frantic, looking everywhere for signs that Cynthia is trying to influence him. He even searches for acrostics. In the end, he finds nothing and is relieved. Readers are too. Until we realize that the last paragraph contains an acrostic: a message from Sybil herself, telling us that she has been reaching out from beyond the grave to manipulate the narrator’s view of the world from the story’s very beginning. Yes, okay. It's a bit heavy. Perhaps I ought to end with a happier tale of the use of an acrostic. A love story. The Moth is a live storytelling event in which people share their true tales on stage in front of an audience. It’s available as a podcast and I listen to it from time to time, especially on road trips. One of the most memorable I’ve ever heard is Cynthia Riggs’ story “The Case of the Curious Codes”. In it, Cynthia describes how when she was 81, she received a mysterious package: an envelop full of cryptograms and a return address given in latitude and longitude. The sight of the cryptograms jogged Cynthia’s memory: at age 18, while working in a marine biology lab, she and a kindly colleague, Howard, used to swap them. He had kept them for 62 years.  Correspondence ensued. The two caught up after so many decades, discovering all kinds of bizarre coincidences, and growing closer with every package. Eventually Cynthia, an avid gardener, received a package from Howard that contained seven seed packets arranged in the following order: hollyhocks, leeks, orka, vinca, eggplant, spinach, and catnip. H-LOVES-C. So having said all that, I suppose there's only one question left, dear reader. Have you figured out my acrostic?

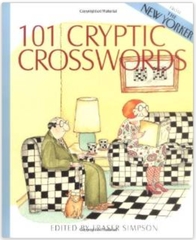

I completely freaked out when I discovered that The New Yorker, my favourite magazine, at one time published cryptic crosswords edited by Fraser Simpson, my favourite cryptic crossword setter. An Amazon search had led me to the collection “101 Cryptic Crosswords: From The New Yorker”, published in 2001, and I couldn’t believe my eyes. How had it taken me so long to discover that such concentrated awesomeness exists? I added the collection to my Christmas wish list (it was December and my mother has spent years drumming it into me that you never buy yourself anything in that month). Then, I counted down the days to the 25th, hoping someone would get it for me. |

About Sarah

I'm a writer, adventurer, amateur setter of cryptic crosswords, lover of "ah-ha!" moments, and exhausted mom. Archives

November 2021

Categories

All

|