In case you weren't already aware, I adore Fraser Simpson's work. His puzzles are clever, precise, and succinct. They have defined my own style as a setter. So you can imagine what a shock it was when I made the following discovery:

His early work isn't that good.

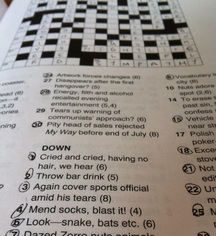

| Don't get me wrong; they are perfectly serviceable puzzles. There are no technical mistakes, and there are the right number of clues per puzzle. But the clues lack sophistication. Here's a recent example: Mend socks, blast it! (4) "I could have written this," I often find myself thinking. And that, it turns out, is an immensely comforting thought. In a talk about storytelling, Ira Glass describes the awkward and humbling period that all creative people must endure when their taste level is high enough to recognize good work but they, themselves, are incapable of producing it. |

| It's easy to get discouraged by the fact that we weren't. So getting to see Fraser Simpson's early work is actually a fantastic gift. If, twenty years ago, his puzzles were comparable to mine, it stands to reason that if I stick with it, my puzzles, twenty years hence, could be as clever and sophisticated as his. And if The Globe and Mail was willing to publish him when he was early in his career as a setter, who knows: I might be in with a chance at a comparable publication. | |

But what I'm curious to know (and you might be able to help answer) is whether this happens in other professions, too. Do young doctors look at their much more experienced peers and think "she's so good; she must have just been born with more raw talent in medicine than me"? Do young researchers? Video game developers? Or do they recognize that so much of what we assume is raw ability actually turns out to be experience? Is there something about being in a profession with more technical aspects, and thus more formal training, that deflates this mistaken assumption?

- Sarah

RSS Feed

RSS Feed